Technical debt isn’t just code (and thoughts on paying it off)

All organizations have some form of it.

Technical debt is the term used to describe the cost of rewriting or refactoring code that wasn't properly designed from the start. It's what happens when speed is prioritized over scalability, or when there are lots of cooks in the kitchen with no clear standards.

Like real debt, technical debt accumulates bit by bit. Someone writes some code, then another person adds to it, and then more additions are made over a period of weeks and months—and suddenly—the codebase is large and unruly. It’s hard to understand, it’s hard to maintain, and the program suffers under the weight of its own inefficiency.

But I think the concept of technical debt can take other forms as well:

- Software that is the wrong fit for where the business is.

- A tech stack that doesn’t work well as a whole.

- Lack of clear processes for managing and curating the tech.

Businesses run on a myriad of software applications. Some of those tools may have worked when the business first started, but now they’re no longer right-sized for what the business needs. Or maybe a simpler configuration, permission schema, or file/folder structure worked well when the staff was small, but now things are a spaghetti mess.

In some cases, the debt takes the form of poor integrations and interoperability between the tools. There’s nothing wrong with each individual tool per se, but taken as a whole, the software stack doesn’t quite mesh well.

Weak procurement processes and a lack of governance can be its own form of technical debt. Without strong oversight on how and why tools are picked, the software stack will inevitably become a hodgepodge amalgamation of tools that promised to solve a problem but didn’t because the forest was lost for the trees.

Addressing the problem

Unlike software, these types of issues cannot be solved by simply refactoring the code. You can’t just rewrite more elegant code bit by bit and make those changes live. There’s nothing you can do to “hot swap” tools and replace them with something better without disrupting business operations. You can't just write a shiny new process and expect people to follow it.

That’s because updating process and tools involves working with people. It's one thing to select a new tool or write a new process. It's another thing entirely to get buy-in and adoption from the people using them. It's easy to pick tools and processes, but they're hard to implement if you don't take the time to bring the users along for the journey. In my experience, this includes the following steps:

- Help stakeholders perceive the real pain of not doing anything. Like frogs in a slowly heating pot, we can get accustomed to sub-optimal tools and processes simply because we work with them every day. The first step is helping stakeholders see the pain of not changing. This could be money being lost, time being wasted, or simply making it harder to make a change in the future.

- Identify requirements. Once stakeholders know they have a problem that needs to be fixed, it's essential to figure out what requirements are for the new tool(s) and/or processes. If you skip this step, you're bound to create more debt that will have to be dealt with in the future.

- Evaluate options. Once you know the requirements, you can evaluate the different ways of meeting those needs. Maybe an extant piece of software can be reconfigured to make more sense with where the business is today. Maybe a new tool is needed. Maybe you need to switch providers for a current application. Or maybe new processes are needed to get people on the same page. The key is to have visibility on the different paths that could help the org get where it wants to be. A knee-jerk reaction to just switch tools or buy another is never wise. (and)

- Build a plan to make the change(s). Once you know what the pain is, what's needed to solve that pain, and what options are on the table, you can build a plan to make the necessary changes. A big part of this is considering what communication and training will be needed for all the people affected by the change. To put it more concretely, I'd say that 60–70% of implementing a new tool and/or process should be invested in communicating and teaching about the change and only 30–40% should be focused on actual implementation.

- Implement the changes and review. After all the key stakeholders are in alignment about the changes and the goals, you can move into implementation. It's always a good idea to evaluate progress throughout implementation to ensure that that changes are meeting the agreed-upon goals.

Sometimes orgs recognize the real pain of not changing, but they do one of two things:

- They make rash changes without considering the total impact of the changes. When the changes fail, the software gets blamed when it was actually a natural consequence of poor planning. That's why steps 2, 3, and 4 above are so important.

- They don't change because it seems "too expensive." If a change is badly needed today, then it's probably going to be worse tomorrow—and more expensive. That's like not fixing a leak in your toilet today because a new hose is expensive. If you let it drip, it will just cost thousands down the road.

Overall, the key to addressing the problem is starting with the people: Think about whose work will be affected, disrupted, or improved by the change. If you start there, the real requirements will start to write themselves, and you'll have a better chance of success paying down these forms of organizational debt and making a positive change. People are the life of an org—the tools are just there to support the people.

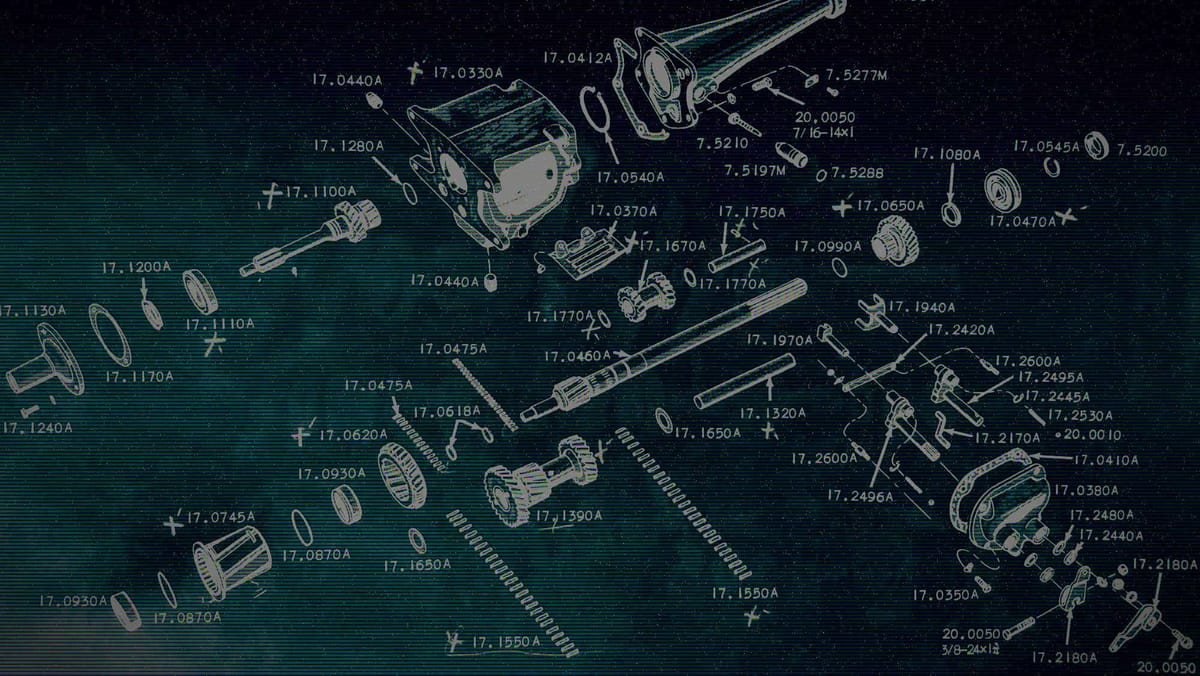

Cover Image: Manipulated photo of an exploded diagram of a transmission in a parts manual I found in the closet in my mom's office. I love those old diagrams and the bird's eye clarity they give on a system's inner structure. I pushed myself to explore the filters and tools in GIMP, and it's amazing what a few tweaks can do for a photo of a page.